Waterloo Street Officers Report

… houses in the area were subject to clearance or closing orders.

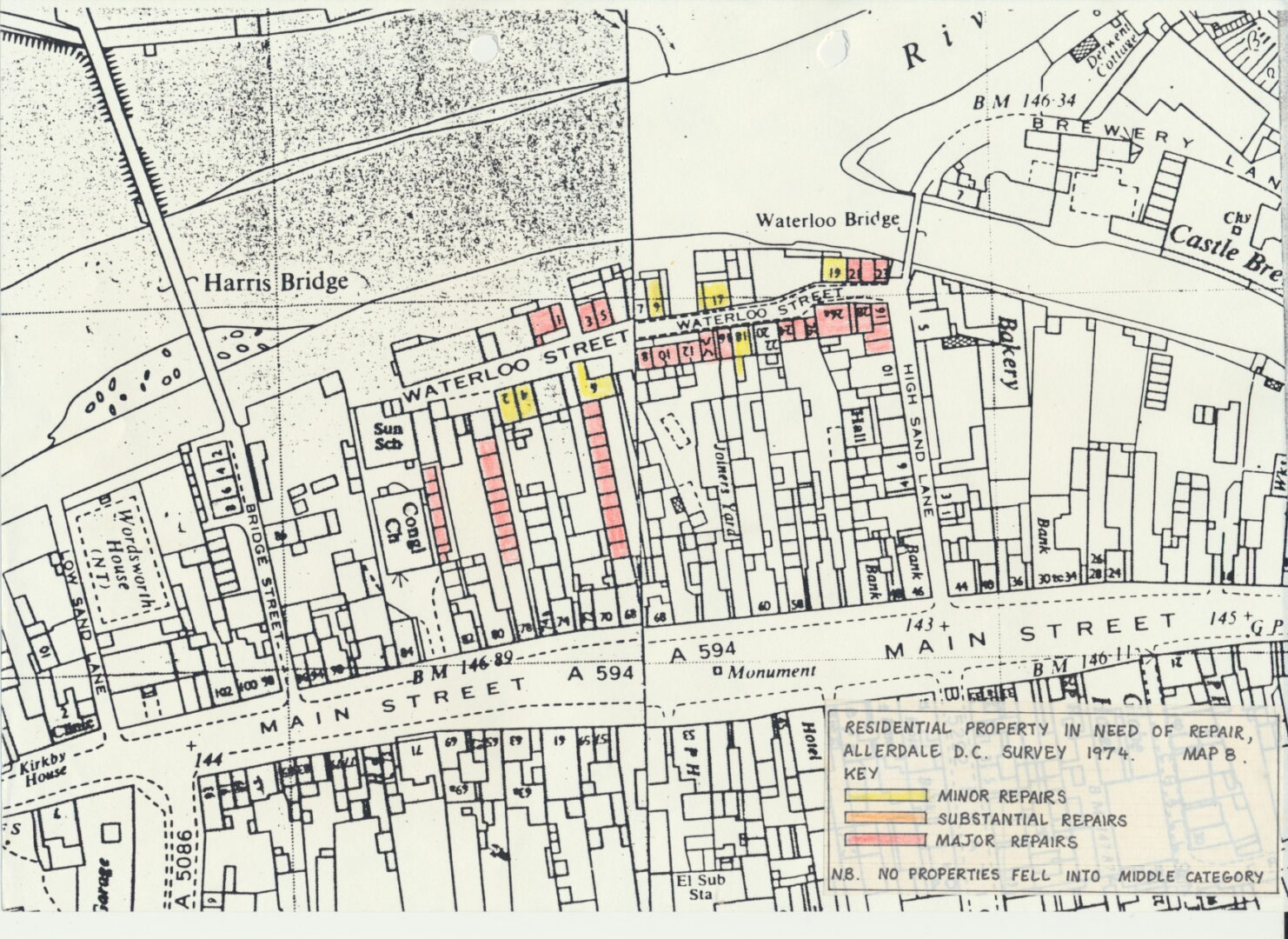

2.6 Map 8 shows the extent to which residential and other properties within the area were judged to be in need of repair and also indicates derelict property as a class for which something more than “major” repairs would be required and where repair as an option was unlikely to be justified.

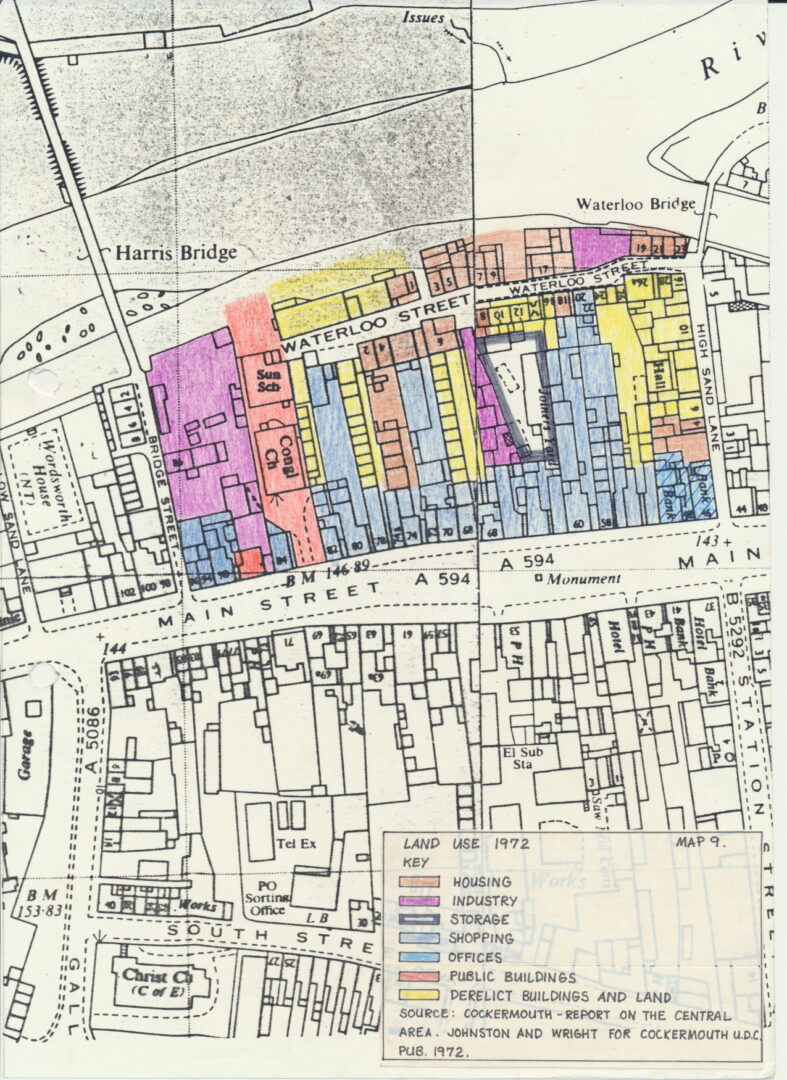

2.7 Map 9 is a land use survey carried out in 1972 illustrating both the hub of industrial and residential uses and the extent of vacant land and buildings. There is an obvious link between vacancy and building condition, though this survey does not attempt to assess whether the buildings are capable of re-use.

2.8.1 Despite the poor physical condition of its properties, the lack of amenities in its housing stock and the problems caused by the land use mix and lack of off street parking, the area retained great visual character and appeal. A report on Cockermouth central area prepared by architectural consultants Johnston & Wright for Cockermouth Urban District Council in 1972 identified the effects of blight and neglect on Waterloo street, but also pointed out that

“The street pattern of Waterloo street and High Sand lane is an historic element of the development of the town…. visually Waterloo Street is of a scale and quality that has considerable merit, notably in the advance and recession of facades and openings along the street”

Photograph 1, taken in 1972, illustrates how elements of projection and recession draw the pedestrian through the area.

Johnston & Wright’s townscape analysis of the Waterloo Street area is reproduced overleaf.

2.8.2 The appearance of the area was determined by a strong vernacular architectural tradition, emphasised by the high density of the urban form. The Cumbrian vernacular style comprises stone buildings with rendered exteriors and steeply pitched roofs clad in local slate. Housing is typified by sliding sash windows of a strong vertical emphasis and panelled doors, both in projecting stone surrounds. The style is extremely simple but unmistakable, relying on the cumulative visual effect of many “ordinary” buildings.

Variety and personalisation are introduced through paintwork, the wall, door and window surrounds and front door being finished in contrasting colours.

Folklore suggests that this use of contrasting paintwork, particularly on the surrounds was intended to keep the devil at bay.

The annotated sketch opposite illustrates elements of the traditional Cambrian dwelling as found on Waterloo Street.

2.8.3 Because of its history, traditional houses and cottages, built in the 18th and 19th centuries are interspersed with former mills and warehouses of the same period. This gave great variety and interest to the streetscape, bringing contrasting massing, height and detailing, within a general uniformity of stone or render finish. Johnstone & Wright identified the powerful contribution to the townscape made by Grave’s and Wharton’s Mills. At roof level slate was again used, but with great variety in form and pitch contrasting with the general simplicity of the cottage roofs.

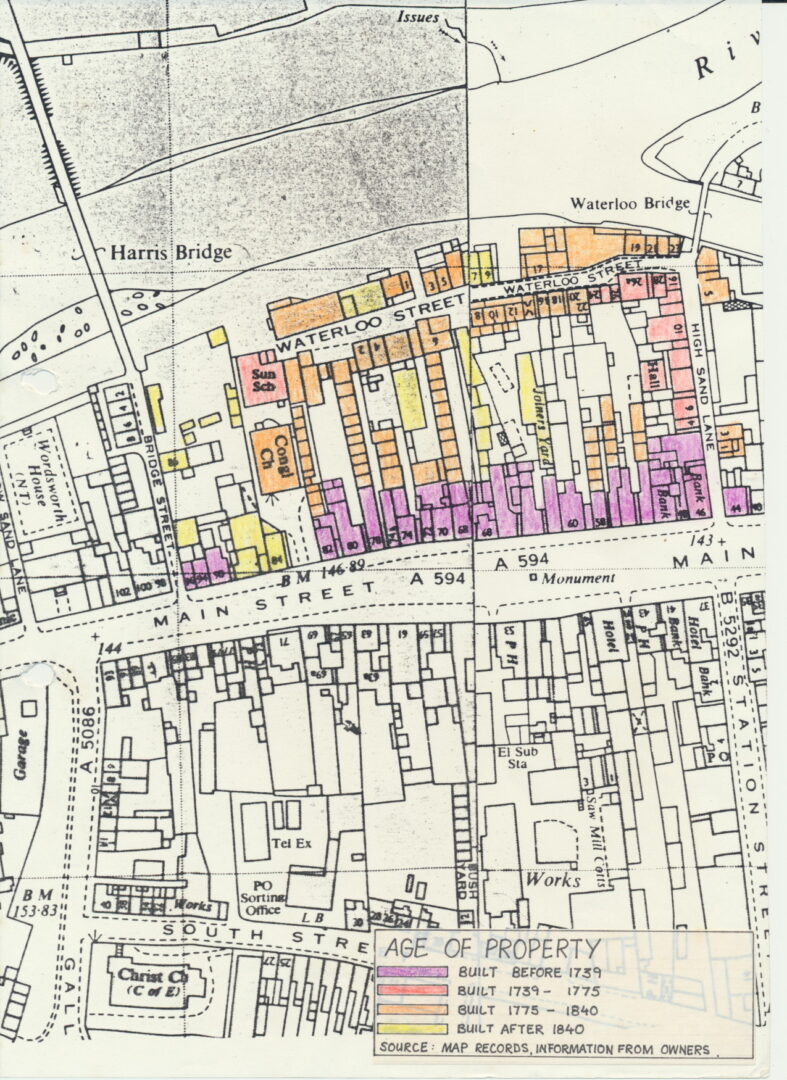

2.8.4 The street, as has been seen, was never formally laid out but developed piecemeal as Main street property owners began to develop their long gardens leading to the river. Development began at High Sand Lane, progressed west to form Waterloo Street and finally a series of Courts to the rear of Main street during a period of about a hundred and fifty years. This development pattern meant not only that the work of a variety of different builders can be seen in details of height, roof pitch and design, but that this was reinforced by changes over time. The townscape area closely and widely reflected its history at every turn with arrangement of scarcely changed 18th century cottages, mills from the age of water power and 19th century courts. The impact was a very vivid sense of tine and of place, the latter reinforced by details such as the beehive motif on Beehive cottage or the unexpected arched window in the former chapel adjacent to 6 Waterloo street.

2.8.5 Elements of projection and recession in the street frontage are similarly explained by this development pattern, in which the street was gradually defined by the erection of individual buildings over a period of time, rather than the buildings conforming to a predetermined street line. This created an interest and expectation which drew the pedestrian on in very much the way Cullen in “Townscape” and Lynch in “The Image of the City” both advocate. Townscape interest was enhanced by glimpses into courtyards, sometimes through arched entrances and glimpses of the river.

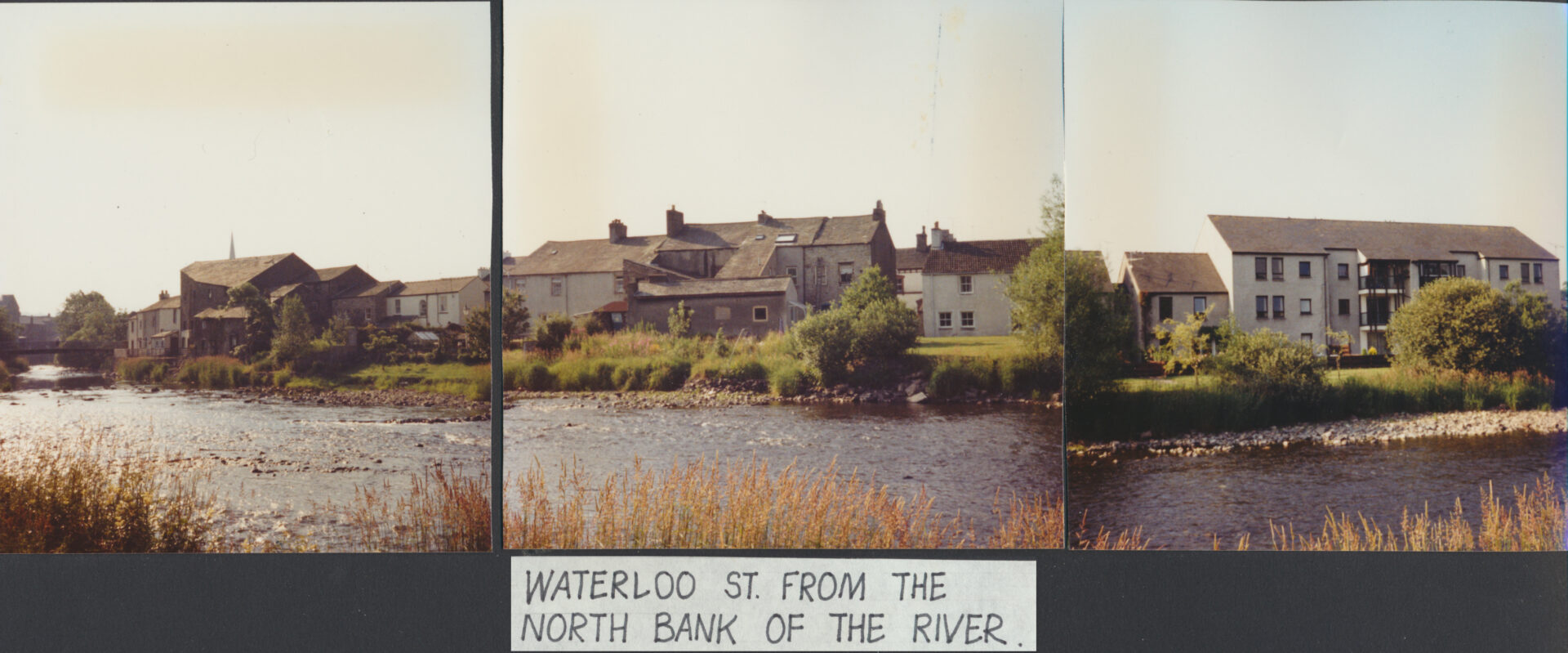

2.8.6 Water can play an important part in the enjoyment of an urban area and Waterloo street took particular benefit from the Derwent, immortalised by Wordsworth’s recollections in the Prelude of a house a few hundred yards away where he played “as an Indian child” on the river bank. Views of the river could be gained from gaps in the Waterloo Street frontage and from the footbridge at the end of High Sand Lane. Although direct access to the water was not possible, it could at times be heard as well as seen, again enriching the experience of the area.

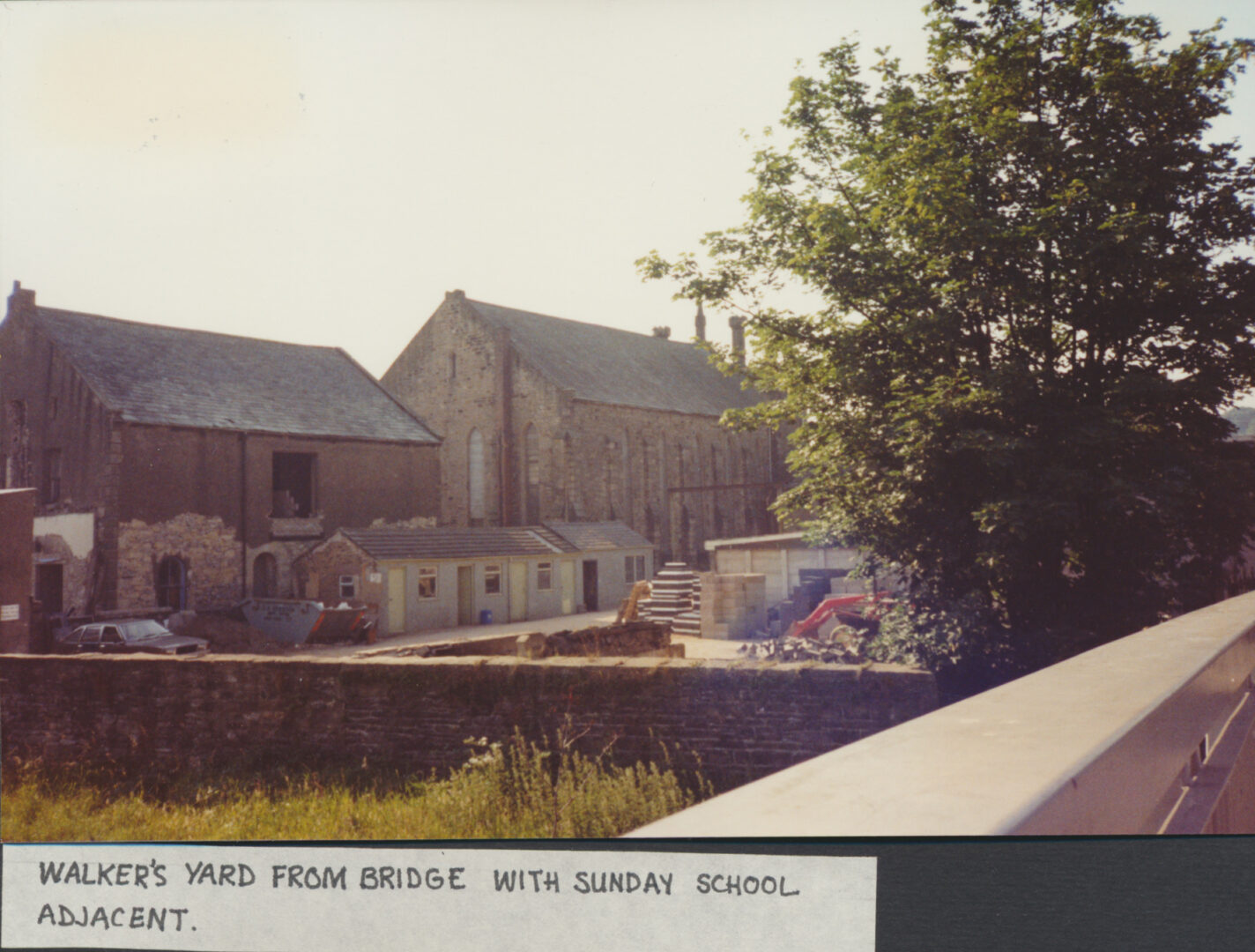

2.8.7 Although the Waterloo Street area’s character essentially came from the value of its buildings as a group, within their setting, certain buildings were of particular architectural or historic interest. These included the imposing 19th century Congregational Church, with its high, turreted facade visible across the area; the Sunday School to the rear, the original church, of 17th century origin but a substantially 18th century building and an important “stop” to Waterloo Street itself; and Victoria Hall, a small chapel, well hidden by buildings but of interest for its 18th century architecture and as a venue where ‘Wesley preached.

2.8.8 Important features outside the area, but clearly visible from it, help fix the appreciation of Waterloo Street within its Cockermouth setting. These include the medieval castle and the brewery to the east and the listed Harris Mill on the northern bank of the River. Beyond the town itself the nearest of the Lakeland fells came into view.

5.4.2 Survey plans reproduced as maps 11 and 12 compared with those prepared in the early 1970’s (see maps 6,7,8 & 9) illustrate the impact which has been made on dereliction during the study period. Discounting those properties where work is in progress, the areas where treatment would be welcome are limited to a former chapel adjacent to 6 Waterloo Street, a group of underused light industrial premises in poor repair to the rear of 62 Main Street, Boots The chemist’s rear yard.

5.4.3 The former chapel was at one time the subject of an application for S10 grant and a tentative scheme for its conversion to flats. The proposal was dropped as a result of the personal circumstances of the owner, the resident of 6 waterloo Street, an elderly person in poor health. Although this interesting building is in deteriorating condition, it may survive long enough for a new scheme to be put forward by a future owner.

5.4.4 Existing business users, small firms unwilling to make large scale investments in their premises, make it unlikely that the yard to the rear of 62 Main Street will be improved in the short term. Nuisance caused by the business is minimal and the Authority has not sought to secure its relocation. The much larger and noisier builders depot and monumental masons premises on Bridge Street, immediately to the east of the Church and Sunday School, cause greater problems and were to have been relocated under proposals for the Waterloo Street Area put forward in 1975. The lack of an alternative site, exacerbated by Allerdale’s failure to implement its own Draft District Plan proposal for a small industrial estate (due to an unwillingness to use compulsory purchase powers), resulted in no action being taken on the matter. This Bridge Street site has ceased to be regarded as part of the Waterloo street Area in recent documents relating to the renewal of this part of the town, perhaps because of this perceived inability to act. Planners anticipate that the unsuitability of the site and its access for commercial use and increasingly high residential land values in the town centre will secure its redevelopment in due course.

5.4.5 The yard to the rear of Boots is undoubtedly a great source of concern both in visual terns and in relation to nuisance caused to Waterloo Street residents by commercial vehicles and staff cars using the Waterloo Street access. The yard itself is open, poorly gravel surfaced and affords clear views of an obtrusive, two storey, flat roofed extension to the rear of the shop. Stone perimeter walls are in poor repair and an inappropriate aluminium gate separates the yard from Waterloo Street. This gate was refused planning permission in 1985, but the Authority had neglected to take enforcement action.

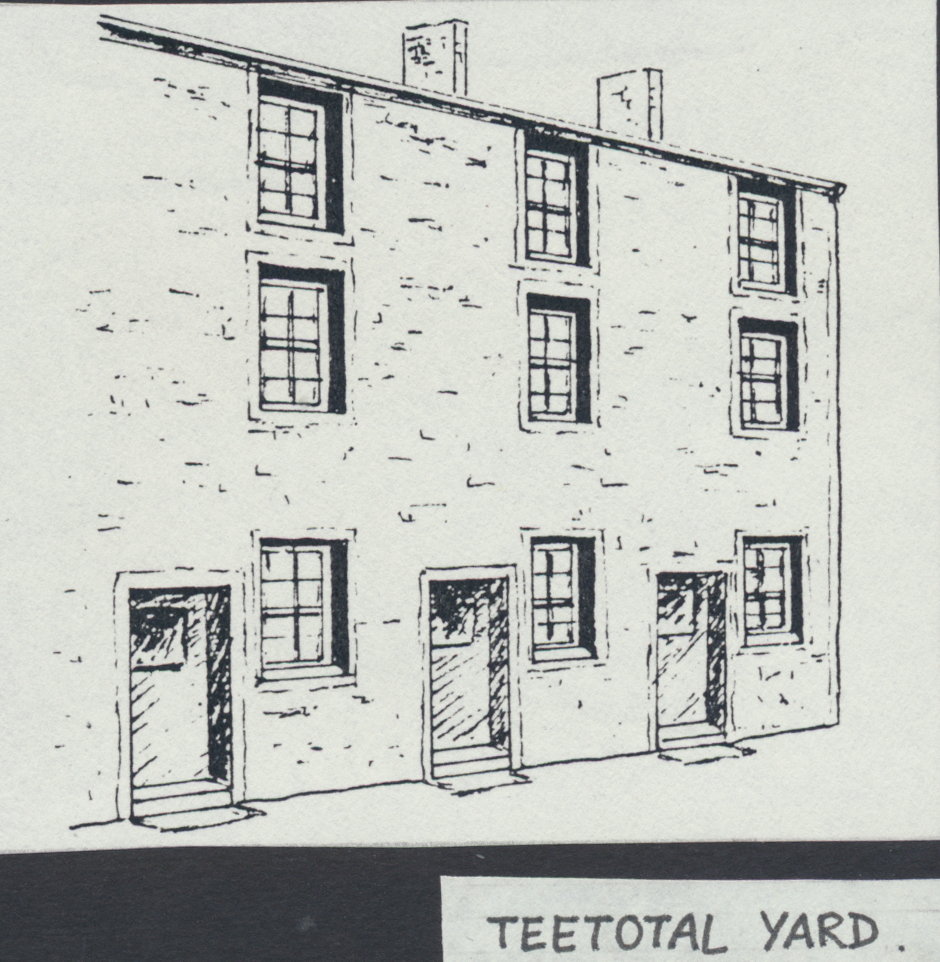

5.4.6 In adopting Johnston & Wright reports findings and proposals for the Waterloo Street area into its own conservation-led policies, Allerdale took. a much stronger line on the value of retaining as much as possible of the built form between waterloo Street and Main Street and abandoned Johnston & Wright’s scheme for a Main Street service access illustrated opposite. It did, however, recognise the need to provide some residents parking facilities within the area and identified two sites, one to the west of the area, incorporating Teetotal Row, consistently judged to be beyond renovation, and one to the east, incorporating part of the Boots Yard (see plans).

5.4.7 Despite protracted discussions with the landowners in question in 1976, public expenditure cutbacks the following year resulted in the car parking proposals being shelved. Expenditure in subsequent years remained at a low level and these proposals, which were likely to involve politically contentious and time consuming CPOs, potentially pushing expenditure forward out of financial years for which they had been programmed, were excluded from the Council’ s budgets in favour of more certain projects. Internal memoranda of the Council suggest strong personal efforts on behalf of the planning assistant responsible for Waterloo Street to change this situation up to the time he left the Authority in 1978. The granting of planning permission for the redevelopment of the site of 6 High Sand Lane, including the site of the projected access in 1981, effectively marked the demise of the eastern car park in its proposed form. Whilst the 1988 redevelopment of Teetotal Row brought the demise of the western car park.

5.4.8 The density of development within the area is such that although all redevelopment schemes, with the exception of sheltered accommodation, has provided one-for-one parking space, residents cars cannot be accommodated within the area. The surfacing and treatment of the Boots Yard together with additional underused land between 24-26 Waterloo Street and 52 Main street could provide an attractive parking area if necessary, available to Boots staff as well as residents during the day. Whilst Allerdale is not a wealthy Authority and public spending limits remain strict it seems unlikely t hat the funding for such a scheme could not be found, given the necessary will.

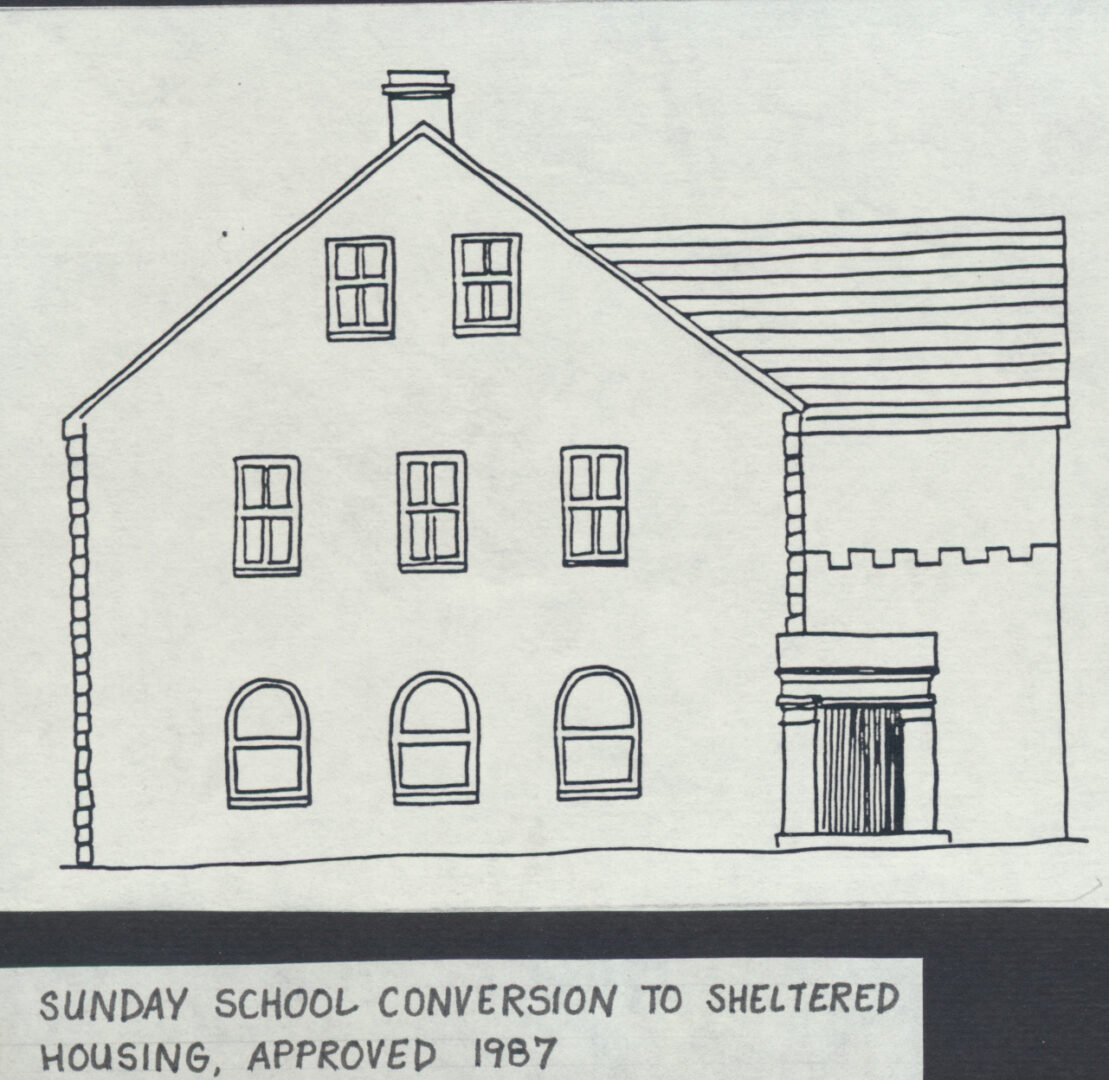

5.4.9 Examining those areas where development has been carried out and looking first at conversion, the scheme to convert the former Sunday School to sheltered accommodation, currently being undertaken by a housing association, must be judged a success in terms of a new use having been successfully found for a listed building, important in the townscape and in terms of the sensitive nature of the scheme which sought to reconcile the building’s character with its new use.

5.4.10 The Victoria Hall, off High Sand Lane, offers another example of a listed building, again an 18th Century Chapel, being renovated through the medium of a new use being found. The scheme involved minimal alterations to the property and is interesting because the developer in this case was the Cockermouth Town Council who now run the building as a community Hall. Allerdale’s own architects were responsible for the plans thought the Town Council itself instigated the scheme and deserves the credit for its success.

5.4.11 Of the two Mill buildings identified by Johnston & Wright as intrinsic to the character of Waterloo street, only one, Wharton’s Mill has successfully been retained. The loss of the other, Graves Mill, is discussed in a subsequent section. Wharton’s Mill is of great visual importance both in Waterloo street itself and in the view from across the river and Allerdale sought unsuccessfully to have it listed. The form and shape of the building convinced planners in 1975 that a residential conversion would ‘be too difficult to ‘be viable, and despite an enquiry from a developer interested in the property as a museum, no proposals for the property were forthcoming until 1988 when a scheme for a sensitive residential conversion was granted planning permission. Work on the scheme has now begun and Section 10 grant is being sought. Drawings reproduced overleaf together with photographs illustrate how well the character of the property will ‘be retained.

5.4.12 A much less happy conversion of a warehouse building on High Sand Lane, again reproduced overleaf, serves as an illustration of how the design values of Allerdale’ s Development Control planners have been modified during the study period. This scheme, approved in 1977, but not subject to Section 10 grant, illustrates how little care was taken to retain and incorporate those features from the original building which added interest and variety to the street scene. The addition of a new-build block in the same style as the conversion at is northern end reinforced the blandness of the facade which is relieved neither by form nor treatment and enlivened only by the plaque describing the warehouse’s fate.

5.4.13 The developing awareness of issues of townscape and a growing appreciation of the contribution made by detail of design and materials in the renewal and enhancement of Waterloo street emerged as a recurrent theme throughout this study in relation to the interpretation of development control policy. .Again setting aside the issue of the demolition of Graves Mill, the new flats on its site granted planning permission in 1980, are undoubtedly the area’s clearest example of a scheme which would not ‘be granted planning permission today. Whilst the architect stated his intention to create a building of scale and massing to punctuate this end of Waterloo Street in the same way as the demolished Mill, the building has little in common with its neighbours in terms of its design or materials and appears visually divorced from them. Neither does the scheme successfully close the vista down the street, nor afford the anticipated public access to the river bank. The relative unity of treatment and approach as Waterloo Street has been revitalised and buildings converted or added since the flats were built has effectively heightened the impact of their inappropriate design.

5.4.14 Paradoxically the image projected by the flats appears to have played a major part in the initial stimulation of private sector confidence in Waterloo Street as a desirable and fashionable address. It is arguable whether, at the time in question, this image would or would not, have been achieved by a far more traditional approach.

5.4.15 The newly built flats on the opposite side of Waterloo Street, on the site of Teetotal Yard, attempt to echo far more closely vernacular characteristics, but also illustrate the dilemma faced by the Authority in seeking to impose much stricter design criteria during a relatively limited timespan. In line with the policy now generally applied within the Conservation Area, Allerdale insisted on the use of sliding sash windows on all facades visible to the public. Top openers have been installed and enforcement action is underway. To the developer’s eye Allerdale is being most unreasonable given the design details of the flats it approved only seven years earlier on an adjacent site. From Allerdale’s point of view to give way on the issue would set a precedent for the abandonment of sliding sashes on other schemes in the Conservation Area.

5.4.16 The importance of this degree of detail in contributing to the character of the Conservation Area is discussed in more depth in section 5.5 of this report.

5.4.17 One area of environmental work identified at the tine of the Johnston & Wright report as being essential was the creation of a riverside footpath which would enable the ‘Derwent to be enjoyed by residents of the area as a whole. The land concerned was already in public ownership and the efforts of the Round Table re harnessed to create a pleasant walkway, its value highlighting the contribution which can be made by voluntary groups with the assistance of the Local Authority. A potential extension to the path, which ‘would have involved the acquisition of additional land by the Local Authority was not pursued, though could not be judged essential. A link to the path at Graves Mill, in townscape terms more desirable, was regrettably not achieved in the redevelopment scheme.

5.5 Objective: The retention of the historic and visually attractive street form of Waterloo Street and buildings and features of architectural or historic interest, or which contribute to the character of the area or quality of the townscape.

5.5.1 This objective is concerned with issues of demolition: firstly the loss of entire buildings, valued in themselves and as elements in defining the form of waterloo Street, where projection and recession of frontages draws the pedestrian on to experience new elements in the townscape; secondly the loss of particular detailed features which add interest and variety to the street scene and help to define a sense of place.

… pages missing …

one Allerdale-owned property on waterloo street, improved in 1977 in line with these principles had top opening windows installed.

5.5.11 As private sector improvements got underway it became usual for both improvement grant and Section 10 grant to be sought on each property and this marked a move towards much higher standards of detailed design control, since the English Heritage (DoE) standard specification reproduced in Appendix 3 , required amongst other things vertical sliding sash windows and solid panelled doors, to be copies of the original, the use of natural materials in all hard surfacing and cast iron rainwater goods. The Environmental Health Department in processing its grant applications for the same properties established close liaison with the Planning Department, initially to ensure that the same item of work was not “double-funded” by the two grants. Familiarity with what would be needed for the English Heritage grant led Health Officers to specify many of the same details in respect of improvement grants in the Conservation Area, even when in the event, English Heritage grant was not sought. Familiarity with the English Heritage philosophy tended to result in an increasingly strict specification. Given that almost all the improved properties in Waterloo street had benefit from one or both types of grant, the overall detailed design standards were drastically improved.

5.5.12 Development control policy took some time to adjust to English Heritage’s interpretation of traditional design, or the need to conserve features at the same level of detail and tended to regard achievements here as a bonus, to be left to the grant incentive’s power. Not until the mid 1980’s did the use of conditions attached to planning permissions to enforce similar requirements begin to be employed as standard practice and by then a high proportion of Waterloo Street renovations were complete.

5.5.13 The worth of this stricter approach to the retention of detailed design features can be seen in the overall unity of the Cockton’s Yard scheme, from its painted panelled doors to its naturally paved and flagged yard areas. Given the importance of this cumulative impact, it becomes important that the same higher standards should be imposed by control rather than being left to the role of grant aid as and where it is accepted. Not all alterations will take place in conjunction with an improvement scheme on a scale to attract grant aid. A common complaint about Section 10 grant has frequently been that the cost of the works required over and above those which the householder intended to carry out, e.g. the use of slates in place of tiles, the requirement for a specially made panelled door or sliding sash window, are not made up for by the amount of grant paid. Only if these works form part of a larger scheme for which the majority of costs relate to items the householder did require, e.g. major structural work, is the householder likely to take up the grant with these conditions, unless they are at the same tine enforced by planning control.