Bridekirk Runes on Baptismal Font and Sentinal Slabs

Baptismal Font. Introduction.

Dating from the mid-twelfth century and probably crafted for the Norman church which replaced an earlier building in 1130, the baptismal font is one of the most unusual and important survivals of Romanesque sculptured stone from the Middle Ages. There is a plaster replica in the Victoria & Albert museum. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner the eminent art historian described the carving as, “one of the liveliest pieces of Norman sculpture in the county… In Cumberland the piece is entirely exceptional”. But it is not only the quality of the mason’s art that makes the font exceptional. It is the inscription in Scandinavian runes with a few English bookhand characters where the language used is early Middle English rhyming couplet that makes the font unique.

Viking settlement in Cumbria was extensive particularly during the tenth century and these Norse settlers brought their runes. Over time the Norsemen would have lost their Scandinavian tongue, or at least were unable to keep it distinct from the English that resembled it but this does not mean that cultural links with Scandinavia were lost, even after the Norman conquest. Survivals of Scandinavian runes in England are rare, but in contrast to any other Scandinavian runic inscription the Bridekirk font bears the only epigraph that is unambiguously English.

Table of Contents

Font: South Side.

On entering the church through the main door the south facing side of the limestone font is seen. Within the lower panel is a roundel or rosette with fluted centre and rope-motif surround, either side are two forms of griffin. On the left-hand side is a classical griffin with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. In Greek mythology the griffin represented the mastery of sky and earth. The griffin first appeared in early Christian art in the early Coptic Church in Egypt in the fifth century and its use spread throughout the Mediterranean and Europe. In medieval England after first being associated with the Devil, the symbolism of the griffin changed to represent the divine human nature of Jesus Christ. Griffins were also thought to prey on those who persecuted Christians. The creature to the right of the roundel is probably a wingless dog-headed griffin with serpent or feathered tail.

The upper panel is of a Greek cross, foliated with acanthus branches. It is thought that foliated crosses (which were particularly common from the eleventh century throughout the Middle Ages) originated from processions held at Easter. Typically a procession would follow the bearer of a plain cross to the church; where on entering the plain cross would be exchanged for a jewelled cross, decked with foliage and flowers, this represented the risen Christ. As a symbol of eternal life this style of decoration is often seen on Medieval tombstones.

Font: North Side.

Carved on the lower north side is a representation of the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist. a nimbus -circlet of light – surrounds the head of Christ, with the Holy Ghost descending, symbolised by the dove. The foliage could be knotted vines bearing fruit, or perhaps trees in a woodland glade.

In contrast to the lower panel, the upper appears to be influenced by the pagan past showing a two-headed monster with serpent-like necks and long tail. Gaps around the monster are filled with foliage and discs, the latter may represent the sun, moon and stars.

Font West Side.

This is difficult to see due to the close proximity of the wall, but the lower panel probably shows Adam and Eve being driven from the Garden of Eden by a sword wielding angel of God. Unfortunately there is some missing detail. It would appear that the man – Adam – was once holding something (shield?) in his left hand. Doubt about the subject matter arises because in early Christian art Adam and Eve are normally shown naked in the Garden of Eden and the figure with the sword is an uncharacteristic representation of an angel. There may also be more missing detail. As a faint outline in front of ‘Adam’ is the shape of a sword falling to earth with the sword handle pointing downwards. If it is not the Expulsion, it is unclear what it is. Could it even be a scene from the life of St. Bridget? Should anybody reading this have any alternative explanation, or clarification for the subject of this scene, please let us know.

In the upper panel there is a centaur (sadly now headless) grappling with an eagle and a beast. Centaurs were first adopted from Greek mythology by the early Coptic Church, but were used in Scandinavian art of the Middle Ages to depict the fight between the hero and the beast, or in English art as the nature of the beast in man.

Font East Side.

Two affronted dragons carved with elaborate peacock tails arching over their backs are seen in the upper band of decoration, separated by acanthus leaves.

In the middle band above the inscription is a scroll of vine branches issuing forth from a grotesque head. with the figure of a man opposite eating a bunch of grapes. a dog or wolf leaps through the foliage. Vines were used as important imagery, as Jesus draws analogies to his life and work: as seen for example in St. John’s Gospel chapter fifteen, also of significance is the symbolism of the fruit of the vine in the form of wine used at the Last Supper.

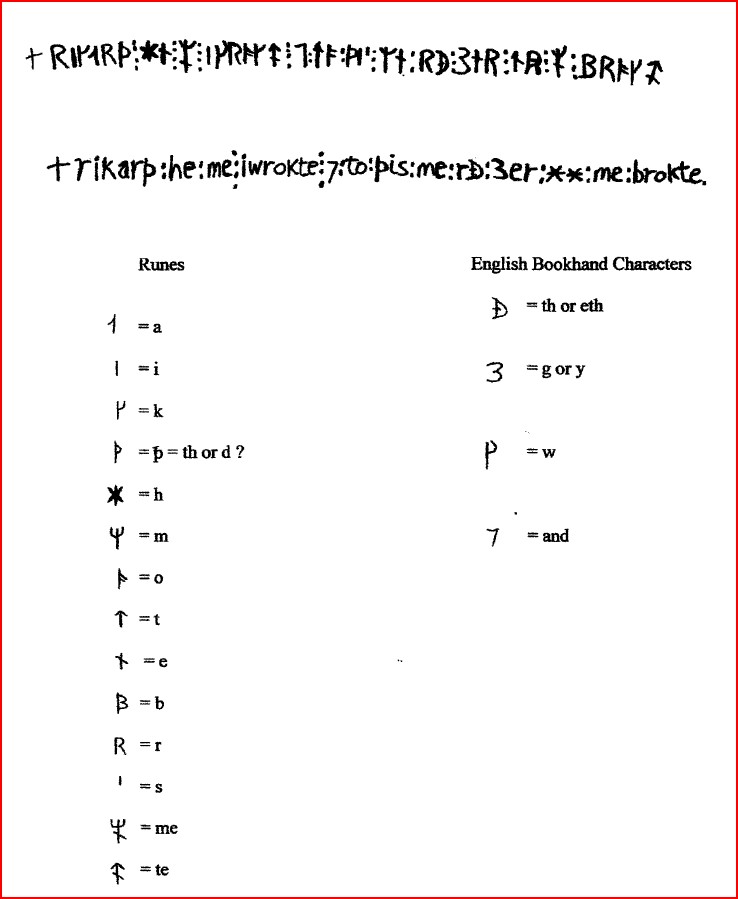

Supported on two pillars and carved into a ribbon of stone is the inscription in Norse runes with some Old/Middle English bookhand characters. The runes are described as being similar to the Man-Jaeren type, which are typical of those used in the Isle of Man and the province of Jaeren in south-west Norway. They also incorporate Danish forms of some runes such as for ‘h’ and ‘m’. Generally the sense of the passage is :

“Ricarth he made me and … brought me to this splendour”.

Alternatively a slight variation on the meaning is:

“Ricarth he [has] me iwrokt [wrought] and this merthr gernr me brokte [to this glorious place carefully brought me]”.

There is a short sequence towards the end of the end of the inscription which has yet to be satisfactorily deciphered by experts, but may be the name of another man who commissioned the font, or the name of the man who painted it. In early years the font would have been painted with a wash of gesso and coloured with pigments.

Some of the runes are partially obscured by the thin skim of plaster” but the vast majority are clearly identifiable, making this perhaps the best-preserved complete inscription of Norse runes in England. There are only about 14 other Norse rune stones in the country most being incomplete, or partially eroded.

Runes were used primarily for inscriptions on stone, metal, bone and wood, but with the latter being perishable few examples remain. In England runes were seldom used for manuscripts because Christian scribes mainly used Roman characters. Following the Norman Conquest inscriptions using Anglo-Saxon runes ended, but forms of some of these runes bad nevertheless been incorporated into script writing. As an example, the Old English bookhand character for ‘w’ seen on the font is an Anglo-Saxon rune form that would have been familiar to those who wrote English. The runic inscription on the Bridekirk font must be one of the last to be made in the British Isles, no doubt due to the remoteness of this area and the large number of people with Norse ancestry who were still familiar with the Norse-Scandinavian futhark (runic alphabet).

Another unusual feature of the font carved below the inscription, is a likeness of the mason at work with mallet and chisel. The name of the mason is either the Old Norse name Rikarthr, first recorded in about 1130 and commonly found thereafter, or the Germanic Ricard, which is recorded in England from the middle of the eleventh century.

Runes – Comment

The runes on the font suggest that the people of Bridekirk still maintained close connections and identity to Norse Scandinavian culture in the twelfth century. Archaeological evidence from excavations at Bergen in Norway have shown that runes were used well into the Middle Ages in Scandinavia by merchants and tradesmen for correspondence, in the form of inscribed sticks of pine and birch. There is a reasonable probability that Norse settlers in Cumbria also used this method of communication for trade locally and perhaps overseas. This might be an explanation for the continued use of Norse runes, resulting in the inscription on the font. From a detailed study by Professor Page of Cambridge University, it is apparent that some of the runes used were of new forms. introduced around the time of the Bridekirk carving. For example, the rune equivalent to ‘e’ (ae) was first used around the year 1150. This indicates continued contact with Scandinavia and a living use of runes, rather than an archaic existence of the runic alphabet passed down in isolation from the first Viking settlers.

Art and language historians have dated the font to 1150, or slightly later, from the inscription, the clothing worn by the carved figures and from the type and style of the other ornamentation. Romanesque period art and sculpture in England was influenced from countries across Western Europe, but there is some very accurate dating evidence from Norway. Carved on capitals of the timber columns inside the Urnes stave church in western Norway are scrolls of vine branches and scallop-shaped leaves or flowers very similar in style to those seen at Bridekirk. A centaur is carved on another capital. The Urnes stave church has been dated precisely by radiocarbon and dendrochronology to 1130. There is a possibility that through trade religious and cultural contacts, some types and styles of Romanesque decoration were used commonly both here and in Norwegian churches.

In deciphering the inscription be aware that the attached sheet showing runes and bookhand characters is an elementary guide only. Modem English words can be deduced from some of the runes, for example: wrought brought, he, me, to, this – but others cannot and are in the realm of expert interpretation. To illustrate this point, in the range of characters 26 to 30 in the inscription sequence there may be the name of another man. Taking one linguistic stem for the name from the first element of this sequence gives Old English Earn…; leading to names such as Gernoberne. or Erneberne. The same element in Old Norse gives Arn. .. ; leading to names such as Arnorr, or Arnthorr, but combined with other characters gives names like Arner, Artur, Arnther and Anther recorded from Middle English sources. Furthermore, another possibility could be Old English, Earnweard, but other records of this specific name do not exist. Finally, if not the name of a man who commissioned or painted the font the word ‘gernr’ (derived from Old Norse ‘gjarn’) can literally mean eagerly, but implying that Ricarthr carefully or diligently “brought me to this glory (‘methr’)”. This inability to be precise about the meaning, or name here, indicates how Old Norse and English languages were probably interrelated by common usage in Cumbria during the twelfth century making exact transliteration difficult today.

Footnote (problematic runes):

Rune 29 is identified as n, or an/na.

Rune 30 is either r or more probably a compound of rune r and the rune I bookhand character shaped similar to the Ietter p. therefore, pr/rp.

Seen below is an approximate copy of the inscription with the Middle English beneath

and some Scandinavian runes and Old I Middle English bookhand characters.

The Sentinel Stones of Bridekirk Church.

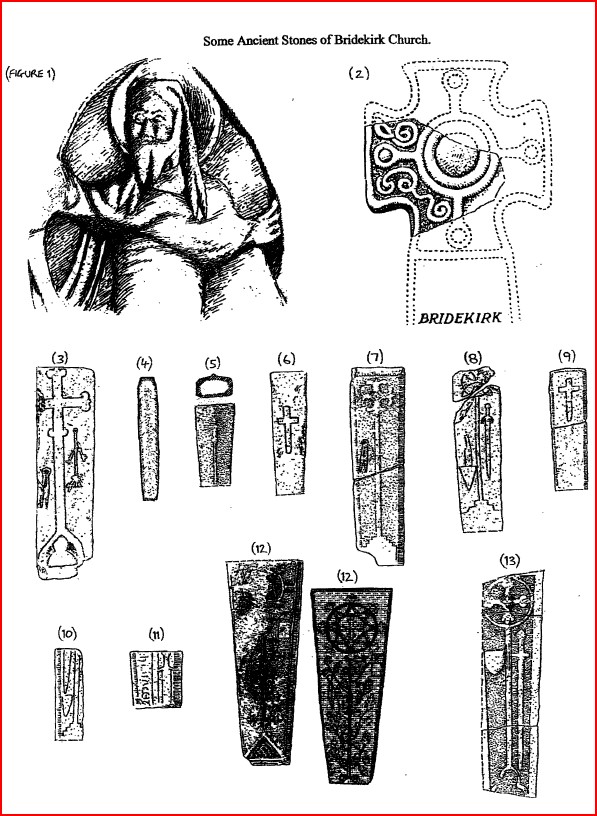

Standing sentinel around the outside apse of the church are ten ancient grave slabs (see figures 3 to 12). The majority display simple carved designs typical of the 13th century. A sword, ploughshare or shepherds crook was for a man, also a sword accompanied by a coat of arms denoted a knight. Shears indicated the grave of a woman, sometimes with the addition of keys. Very occasionally shears were used for the grave of a priest, along with a cross. Priests were more often represented by the symbol of a chalice or a book. Brief details of the grave slabs follow, going in an anticlockwise direction around the apse.

With a cross shaft rising from an arch base and simple fleur-de-lys terminals at the head of the cross, it displays shears and a chatelaine carrying at least three keys (figure 3).

A plain boat-shaped stone, it could be medieval but may be as late as the 18th century (fig 4).

Pawn sandstone slab with splay-arm cross and disc at head of shaft, probably 12th century (fig 5).

Simple rectangular slab of orange sandstone with straight-armed cross (fig 6).

Round-leaf bracelet cross rising from stepped base with shears, probably 13th century (fig 1).

Cross rising nom crude stepped base, with sword and ploughshare – 12th century (fig 8).

Pink sandstone slab with small incised cross (fig 9).

Part of a slab showing cross shaft and ploughshare (fig 10).

Part of an incised slab with cross shaft, sword and inscription ‘hiciacet’ – meaning ‘here lies’ (fig 11).

Resting upside down against the wall is the most important of the grave slabs. It has a high quality relief carved design of a cross, foliated with oak branches and cross head of the interlaced diamond type, with straight-armed cross at the head centre. To one side of the cross is a square tablet representing a book. Opposite the book there was once a pair of shears, which have unfortunately disintegrated, along with much of the cross head, due to the friable nature of the red sandstone. This was probably on the grave of a priest but just possibly it may have been for a nun (figs 12).

To find the final slab, look inside the ruined chancel of the old church, where the grave slab of a 13th century knight has been used as the lintel above the barred window, when the chancel was extended in the 16th (?) century. It has bracelet derivative cross terminals, in something between a trefoil and fleur-de-lys, rising from a trefoiled arch base. There is a long sword on the right of the cross shaft and shield on the left (fig 13).

Ancient Stones of Bridekirk Church.

The present neo-Norman church was completed in 1870. It includes a number of arches and other stone features incorporated from the earlier Norman church, built about 1130 which in turn replaced an Anglo-Saxon church. Apart from the font, there follows a brief description of some of these other details of interest.

Inside the porch is one of the original Norman arches transformed from the old church. Above the doorway is a semi-circular carving known as a tympanum. This dates nom the 11th or 13th centuries when there was a style for carving Christ with a twin-peaked beard. Although eroded by the weather, the head of Christ with forked beard and hand raised in blessing can be discerned. It is thought to represent Christ’s Resurrection or Ascension into heaven (see figure 1).

The stone on the windowsill on the north side of the nave is part of a 10th century Anglo-Scandinavian cross, similar to the cross on the Giant’s Grave at Penrith (see figure 2).

Opinions differ about the origins of the stone on the opposite windowsill between being part of a Romanesque panel or a piece of Roman sculpture. Those who have claimed it to be Roman consider it to be a dedication to the Romano British water goddess Coventina. The full extent of Roman settlement at Bridekirk is unknown but in recent years a small part of a Roman building was excavated just north of the churchyard boundary. Shrines to Coventina were found at freshwater springs, one is known on the Roman Wall. Was there a similar shrine in Roman Bridekirk? (Not illustrated.)

The archway over the door into the south transept is from the Norman church. An ancient stone is incorporated into the wall to the left of the doorway. It bas been cal1ed the ‘Passion Stone’ because it represents the wounds of Christ’s hands, feet and heart. made by the nails, lance and a crown of thorns. Another school of thought recognises it as the ‘Trinity Stone’ depicting the Father (a heart); the Son (open hands in blessing) and the Holy Spirit (a dove). (Not illustrated.)

Ref: Bridekirk Church booklet explaining the church, font and stones.

Bridekirk Font from Bradbury Camden Stukeley

The famous Bridekirk font, with runic inscriptions added in the 12th century, was possibly brought from the ruins of Papcastle. In 1586 & 1607 the historian William Camden wrote in his “Britannia” about

“the carcase of an ancient fort whose Roman antiquity … where among many monuments of antiquitie, was found a broad vessel of a greenish stone, artificially engraven with little images; which whether it had been a Laver to wash in, or a font… for which purpose it serveth now at Brid-Kirke, that is, at St Brigids Church hardby, I dare not say”

Detailed records begin in 1725 when the antiquary William Stukeley picnicked on the site with Humphrey Senhouse and the historian Gale. Stukeley wrote:

“… The famous font, now at Bridekirk, was taken up at this places, in the pasture south of the south east angle of the city, by a lane called Moorwent . .. (Reference to stones, slates and flooring discovered) … . This was a beautiful and well-chosen place, a south-west side of the hill, a most noble river running under it, and a pretty good country about it, as one may judge by the churches; . On the side of the hill are many pretty springs; at one of them we drank a bottle of wine, to the memory of the founders; then poured some of the red juice into the fountain-head, to the nymph of the place. “ [Stukeley 1725 q. E Birley NS63]

Ref:

- Bernard Bradbury, J 1981 A History of Cockermouth. Philmore & Co Ltd. London & Chichester. pages 16-18 Papcastle fort and vicus. [Available from Cockermouth Library and Cockermouth Bookshop 2022]

- Bernard Bradbury, J 1987 Cockermouth in Pictures – 6; Houses.

- Hutchinson, W 1794 The History of the County of Cumberland. Vol II. Page 255

Text taken from The Lake Counties Edited by Arthur Mee 1937. Please write your own observations and descriptions of the villages in present times and email to the editor of this website.